In the nine scenarios I presented, the main characters did not explicitly desire anything contrary to Islam. Rather they all submitted, each in his or her own way, to the only absolutes available to them in those circumstances. It would be both extremely strange and highly unfair to dismiss their efforts in not only reaching but actually lunging beyond themselves to discover the Highest they could find in those critical moments. This is why the saying Truly GOD does not neglect the wages of the faithful is so important. It validates the good choices of the vast majority of humanity who have never had a chance to consider Islam in its doctrinal, systematized form.

On the other hand, the particular form of Submission taught by countless prophets from Adam (peace be upon him) up to and including Muhammad (may GOD bless him and give him peace) constitutes the kind of guidance humanity, in the ordinary course of life, would find most useful in order to be prepared for crises such as imminent death or devastating loss. To knowingly desire some other religion without the same divine imprimatur, despite Submission being the best expression of faith in religious terms, does indeed make one among the losers in the Everafter. How much of a loss does this entail? Is it counter-balanced by the amount owing as wages of the faithful? Only GOD knows what lies within the hearts of His servants, what their motivations are for accepting or rejecting something, and what rewards or chastisement they deserve. We need not, and should not, judge. Our task is only to give good news to the believers. (Q2:223).

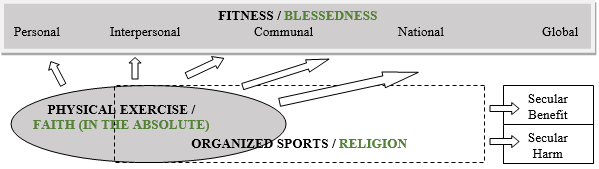

To do so, here is a diagram that illustrates the underlying connections among faith, religion, and admission to the Garden, i.e., blessedness. To clarify their relationships, I am using physical exercise, organized sports, and physical fitness as analogues.

A1) All of us who are living are engaged in physical exercise, even if by the mere motion of our heart and lungs, and to that extent we are ‘fit’, i.e., fit for life. This is not, of course, what we normally mean by physical exercise or fitness.

A2) Every living thing needs faith to function in an environment replete with both excess information and uncertainty. The simple act of processing sensory data requires a modicum of affirmation, of choosing ‘Yes’ and determining ‘No’. When the Qur’an mentions faith (iman), however, it is usually (but not always) understood to be faith in God.

The outcome or reward for faith in God is blessedness. Consider this to be like positive feedback from AL-LAH, motivating us to continue seeking and striving. It is not quite the same as happiness or pleasure,* for a believer will persevere in her faith even at the cost of pain, sorrow, disappointment, and death. But in doing so she becomes fit for life – the ‘other’ life, that of the spirit.

* One of the absolutes that culminate in GOD is happiness. To be with AL-LAH is to dwell in the Home of Peace (daris-salam), and Peace (As-Salam), which also means soundness, well-being, and safety in Arabic, is one of GOD’s Beautiful Names. In one sense, GOD is Happiness – Absolute Happiness, and thus utterly beyond our capacity to comprehend or even enjoy in full.

As an absolute, therefore, and as a kind of metaphor for GOD Himself, happiness certainly has a part to play in any complete account of the Qur’anic weltanschauung. To the extent that a person aims for happiness in seeking the Pleasure of AL-LAH (Q2:265), therefore, utilitarianism is compatible with the ethics of the Qur’an.

But utilitarianism is not content with recognizing the importance of happiness for all (“for all” distinguishing it from hedonism, which is happiness for just oneself). Rather it prescribes utility as the standard in all ethical judgements, as per its leading proponent, J.S. Mill:

The creed which accepts as the foundation of morals, Utility, or the Greatest Happiness Principle, holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. By happiness is intended pleasure, and the absence of pain; by unhappiness, pain, and the privation of pleasure.1

From an Islamic perspective, there are three basic problems with this approach:

1) Happiness is an absolute, like beauty, knowledge, and power, but there are other absolutes that are intrinsically ethical, such as justice. Happiness as Mill uses it, however, derives its value from his rating it as a measurable fact, which he hints at by the word “proportion”. In Chapter 27 and Chapter 34 (which follows this one), I argue that values, including ethical ones, cannot be derived from facts.

2) Utilitarianism is a special form of consequentialism, in which the worth of actions is judged solely by their consequences. But the foundation of Islamic ethics is the famous hadith: “Actions are only [judged] by intentions . . .” (Hadith 1, 40 Hadith an-Nawawi)

3) In Utilitarianism, Mill struggles with the issue of how to assess various kinds and degrees of happiness. He is forced to admit into the discussion an element that he must on principle exclude, namely quality, as we see with his “better” – It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied.2 Not only is this “better” both disputable and incalculable, in the light of an eternal Everafter and GOD’s perfect knowledge of what is useful, all utilitarian calculations are futile. And without such calculations, utilitarianism is useless.

And if you were to count the bounty of AL-LAH, you could not reckon it. (Q14:34)

وَإِنْ تَعُدُّوا نِعْمَةَ اللَّهِ لاَ تُحْصُوهَا

B1) Physically fit individuals are, all else being equal (ceteris paribus), better persons in general, and their being fit is a positive influence on their relationships, on their community, on their country, and on humanity as a whole. That influence is even more likely to be productive when magnified by the interpersonal and communal bonding inherent in organized sports.

B2) Having faith in the Absolute is not the same as having a religion. While ‘religious’ people can be all the various grades of humanity that we see in religions today, including some of the very worst specimens imaginable, a believer in the Absolute is, by definition, someone oriented to the highest aspects of his own character and at least some of the highest ideals of his time and place.

Insofar as all of us must believe in something, we are all believers. But to have faith in the Absolute is to reach above oneself to the Supreme Good. That tendency, ceteris paribus, can only be positive, no matter how one names that Good. The original purpose of religion is to magnify and concentrate this tendency through unified, communal striving and commitment.

C1) Physical exercise can be either individual, uncoordinated with others’ activities, or performed in a social milieu. Most social contexts for physical exercise are organized to a greater or lesser extent, and some, such as professional football matches or badminton tournaments, are highly regulated and usually involve spectators, various officials, and auxiliary and service staff. Participants are often more motivated to be physically fit in an organized context than individually.

C2) While faith is individual activity, no one’s faith operates in a vacuum. Our social and cultural environment, our predispositions from birth, and the particular events that shape our character (and GOD is implicated in all of these) help determine our capacity for faith and what type of faith it will be. Faith requires effort; we need all the help and motivation we can get to maintain and strengthen it. Religion provides that support.

But religion in any form comes at a cost, namely conformity to the rules and attitudes that make it organized, effective, and identifiable. Initially a reference point and safe harbour for the faithful, religion eventually develops the protective structures that make it an institution and a system. Increasing numbers begin to take shelter in it, and soon consider faith to be a product of the institution rather than its living source and final cause (i.e., reason for being). As religion looms ever larger and faith becomes ever more obscure, more and more religious participants fit into it without themselves being spiritually ‘fit’. Many make a living out of it or find comfort in it, and there are others who take part as onlookers and nominal members, without any real commitment or effort other than ‘going through the motions’.

D1) While all physical exercise, including participation in organized sports, results in fitness, there are non-physical aspects of organized sports that produce various beneficial and harmful side effects. A football stadium, for example, provides income for a large number of groundskeepers, food vendors, security personnel, etcetera. Football fans develop a feeling of solidarity with their like-minded neighbours, performing acts of generosity and compassion that would not occur otherwise. At the same time, their communal cohesion could produce malignant feelings towards other teams’ supporters. Their emotional involvement could contribute to drunkenness, vandalism, riots, and even wars. Sports usually offer a safe outlet and diversion for the wanton energies and pent-up pressures in the population, and are generally considered one of the best means for training and shaping the character of youth. But a national obsession with sports probably means other problems are not being properly addressed.

D2) Religion, likewise, has a ‘spillover’ effect, regardless of the actual faith of its members, by virtue of the social capital it generates. Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist with a secular, liberal mindset, explains this in a chapter entitled ‘Religion is a Team Sport’, where he quotes a conclusion reached by two political scientists, Robert Putnam and David Campbell:

By many different measures religiously observant Americans are better neighbors and better citizens than secular Americans – they are more generous with their time and money, especially in helping the needy, and they are more active in community life.1

Like sports, marriage, commerce, and almost all human activities and institutions, religion has a dark side that only faith can control. When its adherents’ faith declines, these shadowy aspects become ever more pronounced. But to ignore the vast and documented benefits of religion through the ages and to consider eliminating it on account of its negative side effects would be like banning sports because of its match penalties, injuries, and occasional riots, or outlawing marriage due to instances of domestic violence. As Haidt argues in his book,

Religions are moral exoskeletons. If you live in a religious community, you are enmeshed in a set of norms, relationships, and institutions that work primarily . . . to influence your behavior. But if you are an atheist living in a looser community with a less binding moral matrix, you might have to rely somewhat more on an internal moral compass . . . That might sound appealing to rationalists, but it is also a recipe for anomie . . . We evolved to live, trade, and trust within shared moral matrices. When societies lose their grip on individuals, allowing all to do as they please, the result is often a decrease in happiness and an increase in suicide, as Durkheim showed more than a hundred years ago.

Societies that forego the exoskeleton of religion should reflect carefully on what will happen to them over several generations. We don’t really know, because the first atheistic societies have only emerged in Europe in the last few decades. They are the least efficient societies ever known at turning resources (of which they have a lot) into offspring (of which they have few).2

Religion, Haidt argues, has survived and flourished because it offers what moral societies need to function effectively, namely a transcendent, unquestionable authority. Of the many communes that were founded in America over the past hundred years or more, the longest-lasting were those that demanded a higher degree of discipline and subordination from their followers – the religious communes. In the same way, he contends, the most effective societies are those that have the strongest sense of unchallengeable values, to which all members can turn as a common goal and reference point. Religions are the vehicles that translate these values into rituals, communal acts, and commonly held beliefs. And transcendence is the glue that binds them all together by virtue of its higher authority.

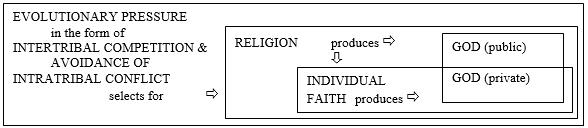

All this is true, as far as it goes, but these basic observations are then harnessed to the modern evolutionary narrative by which everything uniquely human, such as religion, art, music, and language, are ultimately explainable in terms of their competitive advantage and survival value. As a social psychologist, Haidt thinks that this account makes wonderful sense of an otherwise inexplicable feature of human society, i.e., religion, and so disagrees with contemporary atheist commentators who consider it maladaptive and archaic.

If we view religion as a device by which tribes or clans gain the cohesion and enthusiasm they need to prevail over competing groups – a process that can be referred to as ‘group dynamics’ – we have, Haidt would argue, a sufficient justification for the role that religion has played in human history. Believers in the Qur’an cannot deny this function of religion, for there are plenty of verses and ahadith that emphasize these same features of din. But where does this explanation lead us? Secular thinkers like Haidt point downwards, to the struggle for survival, as the root cause of religion and all the other aspects of culture that distinguish us from animals. Believers point upwards, to GOD as the Source of everything in our environment, including religion, that leads us back to Him.

The secular narrative can be represented roughly this way:

On this showing, ‘God’ is an intellectual product in the mind of the individual believer and/or an object of communal faith in a religion, which is a device generated from the pressure to maintain a cohesive community and out-compete rival tribes. ‘Evolution’ is the greater frame in which all of this takes place, and thus satisfies the demand of science for a theory that elegantly accounts for human history and spirituality in terms of lifeless matter and mechanical algorithms.

Does the Qur’an have a cogent reply to this reductionist argument? What does GOD have to say to those who repackage Him as a small thing inside of a box (faith) inside of a box (religion) inside of a box (evolution)?

1 J.S. Mill, from Volume 43 of the Great Books of the Western World, Utilitarianism, p. 448.

2 Ibid., p. 449.

3 Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind, page 267.

4 Ibid., page 269.