One difficulty in contemporary discussions of the Qur’an is that what was obvious and non-controversial in former times is not necessarily so today. The first textbox in Chapter 7 provides two examples of how our understanding of creation and humanity can expand as our scope of reference in time and space has broadened, thus introducing new questions and perspectives into the distinction between clear and unclear. Let us take a look at another pair of examples.

He is the One Who starts creation, then – and what is easier – repeats it. In the heavens and the earth is His most lofty metaphor. He is the Mighty, the Sagacious. (Q30:27)

وَهُوَ الَّذِي يَبْدَأُ الْخَلْقَ ثُمَّ يُعِيدُهُ وَهُوَ أَهْوَنُ عَلَيْهِ وَلَهُ الْمَثَلُ الأَعْلَى فِي السَّمَاوَاتِ وَالأَرْضِ وَهُوَ الْعَزِيزُ الْحَكِيمُ

At the time of revelation in the seventh century C.E., the heavens meant the seven heavens frequently mentioned in the Qur’an, and which were commonly considered to be the paths of the seven classical ‘planets’, namely the Moon, Venus, Mercury, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. The earth was understood to be either a flat mass of land and water at the ends of which the Sun and Moon rose and set, or, in the Ptolemaic system, a globe around which all the ‘planets’ revolved.

Our contemporary viewpoint is, of course, quite different. The Sun and Moon are not planets at all, and only the Moon orbits the Earth. The Ptolemaic system is outdated and simply wrong. The seven heavens were either mentioned so as to conform to the common assumptions of the time – in which case reference to them in the Qur’an is obsolete as well – or, as I believe, they signify what was meaningful to readers of that time in one context, with their level of understanding, and remain meaningful to us today, but in a different context and with a higher level of abstraction. (This is yet another example of how the same word or expression can have different meanings simultaneously, for what is true at the symbolic level now was true in the past as well.)

References to the earth, likewise, that may have been understood in a physical, literal sense in the past have currently to be reconsidered within a broader frame. The travels of Dhil-Qarnain in Suratil-Kahf, for example, must now be interpreted rather more symbolically than before, given that he is mentioned as arriving where the sun set (Q18:86) and where it rose (Q18:90). Needless to say – but for modern literalists it has to be said nonetheless – there is no place on earth where the sun does not set or rise, making all places alike in that regard, and so these expressions require a certain latitude (or rather longitude) in interpretation, for example ‘as far west as he could go’ and ‘as far east as he could go’.

If we ask, therefore, ‘What does GOD mean by the heavens and the earth?’ the answer could be each and all of the following: 1) a concession to the ancient physical cosmography of a flat earth and seven layers above it or the Ptolemaic system of concentric spheres around the earth at their centre; 2) a reference to our contemporary cosmography, physical and informational, comprising vast expanses of space (the heavens?) and our current (and only?) home planet, Earth; 3) a symbolic and multi-dimensional conceptual system wherein ‘heavens’ and ‘earth’ acquire their meanings from allusions in the Qur’an – a frame broad enough to include both materialistic schemes in 1) and 2).

Many commentators consider the heavens and the earth to be the Qur’an’s standard expression for indicating the entirety of creation. But in (Q30:27), quoted above, they are referred to as GOD’s most lofty metaphor. The word metaphor itself is a metaphor, coming from a Greek term meaning to “transfer” or “carry across.” Metaphors “carry” meaning from one word, image, idea, or situation to another . . .2 If the heavens and the earth constitute all of creation, then what else is there that this expression could be ‘carried’ to, and what entitles this particular figure of speech to be considered the most lofty?

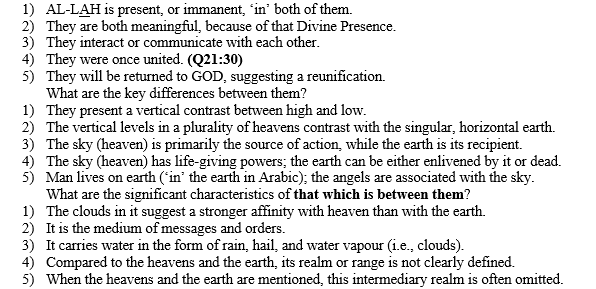

From the following table, we realize that references to the heavens and the earth and that which is between them provide a template for a wide range of meanings in numerous contexts. These contexts interact like the interchange of winds (Q2:164) or the fecundating breezes (Q15:22); they transpose the basic pattern of two contrasting realms into new fields, and bring back from those fields fertilizing connotations of what the heavens and the earth and that which is between them could be saying to us at various degrees of implicitness and symbolism.

What do the heavens and the earth have in common?

This whole ensemble of meaning is what AL-LAH refers to as His most lofty metaphor. But what could be loftier, besides GOD, than the literal, created heavens? It must be the heavens of the order or command, the Word that overrules creation to give it a particular direction or meaning: Truly His are the creation and command. Blessed be AL-LAH, the Master of the worlds! (Q7:54) We see it at work here: Verily the likeness with AL-LAH of ‘Isa is like that of Adam; He created him from dust then told him “Be!” and so he came to be (Q3:59); and we see it in the extended passage of Q41:10-12, in which GOD first created the earth and then turned to the sky while it was smoke, ordered it and the earth to be obedient, and ordained the sky as seven heavens and inspired in every heaven its command. Both the heavens and the earth are created, i.e., are things, but there is an additional, verbal element of arrangement and command that distinguishes both the heavens and the activation of every creature (not only ‘Isa and Adam, but all things as in Q36:82).

We could say, in short, that creation is GOD’s basic language, expressed in material forms (dust or clay), and then superimposed on that is the effective language that empowers, enlivens, and directs, expressed in words, communicating a higher reality that arranges, regulates, and commands. We see the same word, sawwa, used for the formation of the human being after his creation (Q32:9 and 15:29) and the formation of the heavens after His creative work on earth (Q2:29). One could truly call the seven heavens, on the one hand, and the spiritual capacity in man, readied for the breath of His Spirit, on the other, as analogous sharers in GOD’s inspired second thought.

With this framework in place, we can now turn to the Qur’an’s first and foundational story of what constitutes reality.

2 From the entry in Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metaphor